Read below, or listen to an audio version of this essay:

I. Beginnings

It came from the Far West, West of West, where it turns East. It came from the islands of Hawaii, those lone cowboys isolated on the Pacific prairie. Mexican vaqueros hired to tame the land, Portuguese sugar cane workers, guitars in hand, handing them to Hawaiians, who untame them. They turn the guitars sideways, set them on their laps like blankets or babies. Tuned them “slack,” the strings hovering high above the fret board. There’s Joseph Kekeku, a Hawaiian teenager who found himself in Utah with his Mormon-converted parents, walking a lonely path along railroad tracks. Notices something shimmering in the sun—a railroad spike. Picks it up and tries it out. This piece of metal in the left hand, sliding up and down the frets, accompanying Hawaiian folk songs with a strange sort of crying. Alien.

It is a traveler, sliding between notes and cultures. Time and distance slurred. It bucked Hawaii and headed East, towards the conqueror. Enterprising Americans sought to capture this strange sound on a new invention, the recording. Would you get a load of this, the records and depictions full of racist caricatures, occasionally capturing something close to the truth. This odd island backwater and its odd sounds. But Americans loved it. It cried somewhere deep, filling the body with an alien voice. That sliding thing—finding the notes in between notes, slurred, sluggish, angelic, demonic—is so un-European, which prefers its even temperament and well-defined categories. That sliding thing is American, maybe trans-merican. Transcendent: seeking to break out and blur together.

Sol Hoʻopiʻi, born in Honolulu in 1902, the 21st child, learned ukulele by the time he could walk and the steel guitar by his teenage years. Fame beckoned on the mainland, where his Hawaiian idols Joseph Kekeku, Pale K. Lua, and David Kaili had already ventured. At seventeen, he stowed away on a ship bound for San Francisco. When discovered, he played his way out of trouble and garnered enough tips to pay his fare. On his recordings, first made in Los Angeles in the mid 1920s, you can hear why: he’s a showboat, stabbing up and down the guitar’s neck, the joy unconfined. Hoʻopiʻi was one of the first to translate jazz clarinet and horn runs for the steel. These trills and swoops in turn codified the steel’s language for country musicians like Jerry Byrd, who liberally borrowed his tricks when playing with Hank Williams, Ernest Tubb, and others.

Sol Hoʻopiʻi’s Novelty Trio - “Farewell Blues” (1926)

In this new borderless land the steel guitar traveled. Non-Hawaiians wanted to play it and correspondence courses obliged, carried by door-to-door salesmen. The Oahu Publishing Company ran 1,200 teaching studios across America. In Texas, the lap steel collided with electricity; now amplified, it rose above the din in noisy dancehalls and honky-tonks. The first recording of an electric guitar was a steel, played by Bob Dunn in Milton Brown and His Musical Brownies.

Further southeast, blues musicians carried their own form of slide technique from West and North Africa and merged it with this Hawaiian invention. It crept into Black churches, lifting congregations to greater spiritual heights. In the ‘40s, foot pedals were added to the steel, allowing the performer to easily transgress different keys, notes, styles, and sounds without retuning. The whole body is required: hands, feet, knees, all working together.

Within the strict confines of country music, the steel guitar carved its own space. A generation of lap steel maestros cut the first trail. That’s Hawaii-obsessed Jerry Byrd on Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” and “Lovesick Blues.” Byrd shadows Hank’s cries with sobbing, sliding tones, sometimes short and sharp like barbed wire, sometimes long and drawn out like the whippoorwill Hank likens himself to. Country music comes from spaces where people feel small: ranches, hollers, plantations. Crying, whining, haunting, hovering, the steel fills that space.

Hank Williams - “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” (1949)

II. The New Country

The pedal steel is an alien spacecraft, zooming horizontally, bending, breaking our hearts by being breathtakingly smooth, but it is not easy to play. It can go anywhere melodically, but it’s still tethered to the tunings of the musicians around it. Fretting a guitar is simple: finger to fret, flesh making contact with metal and wood. Playing a pedal steel is alchemical: the hand doesn’t have to move to change chords. When it does move, the hand must be exact or risk straying into dissonance. There is a price to so much freedom.

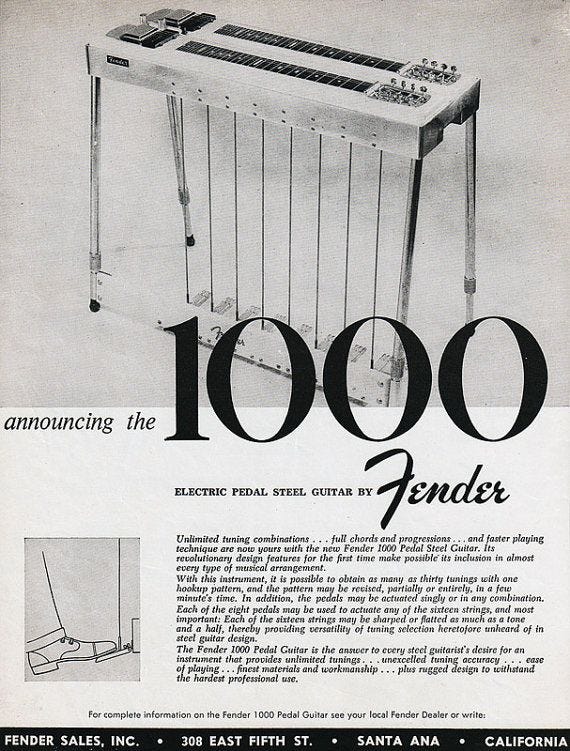

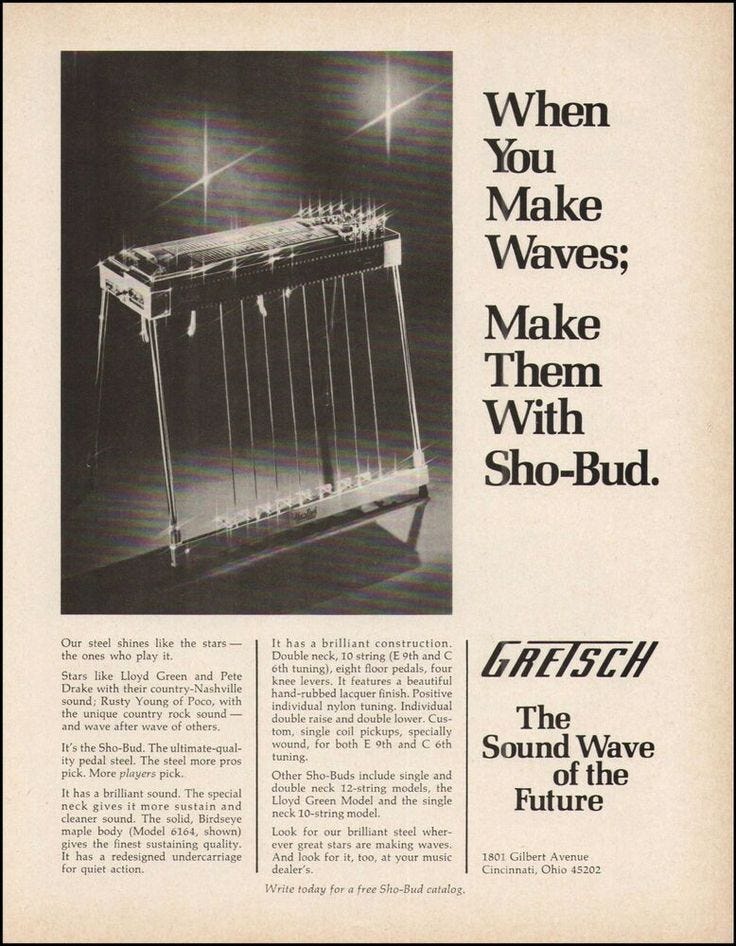

“Sitting at the pedal steel is about as sexy as sitting at a sewing machine,” writes Ginger Dellenbaugh. It’s a piece of furniture, placed at the back of the stage next to the drummer. Even the brand names sound furniture-adjacent: Emmons, Sho-Bud, Excel, Fessenden, Electar Zephyr. Yet the pedal steel is a beautiful thing, complexity simply arranged, with straight horizontal and vertical lines intersecting each other, the player forced to mimic the same formation with their body. Wood covered in chrome, reflecting light like a rocket ship, a flying saucer.

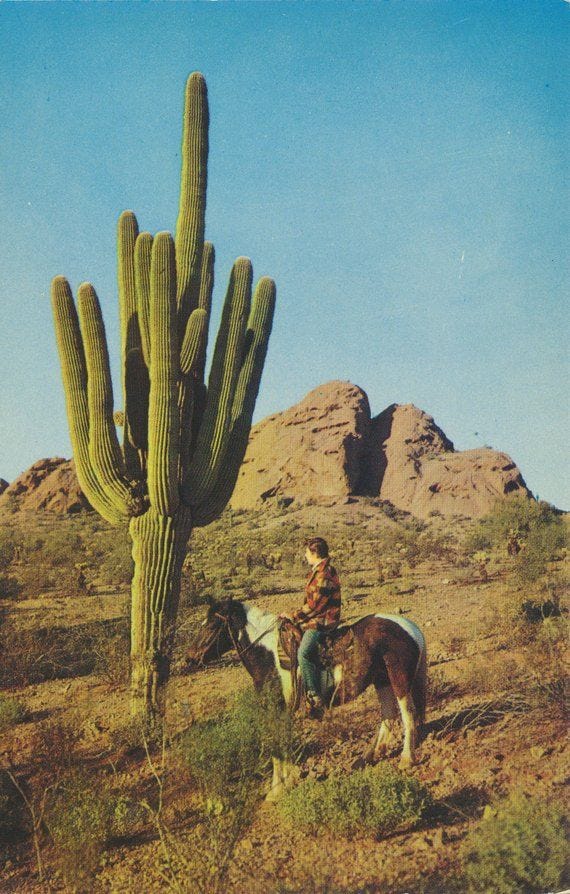

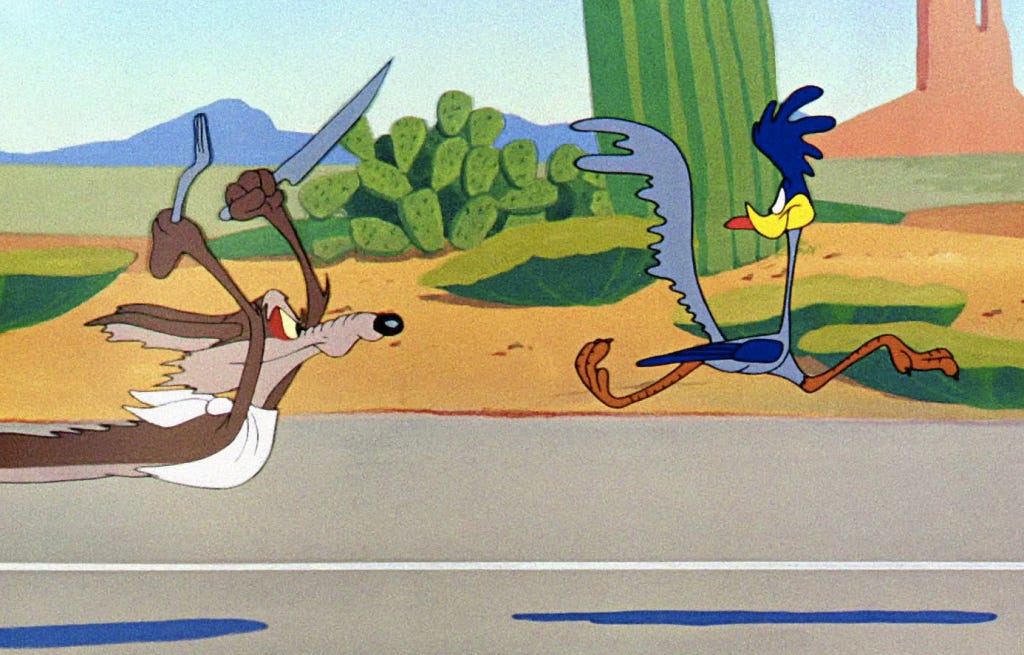

The steel guitar came from Hawaii, kicked around America’s nooks and crannies, but firmly touched down in the American West of the imagination. What better instrument to traverse all that space? The guitar gallops like a horse, the pedal steel glides smoothly like a chrome-encased car on the new interstate highways. Technology harnessed in the service of saving time. There’s Speedy West, literally “Speedin’ West” in 1960, on the drivetrain of hot-rodded jazz licks. His steel blurts, swoops, hot dogs, does donuts in the middle of the road. Cactus, Roadrunner v. Coyote, the strange new shape of Sputnik hurtling overhead.

Speedy West - “Speedin’ West” (1960)

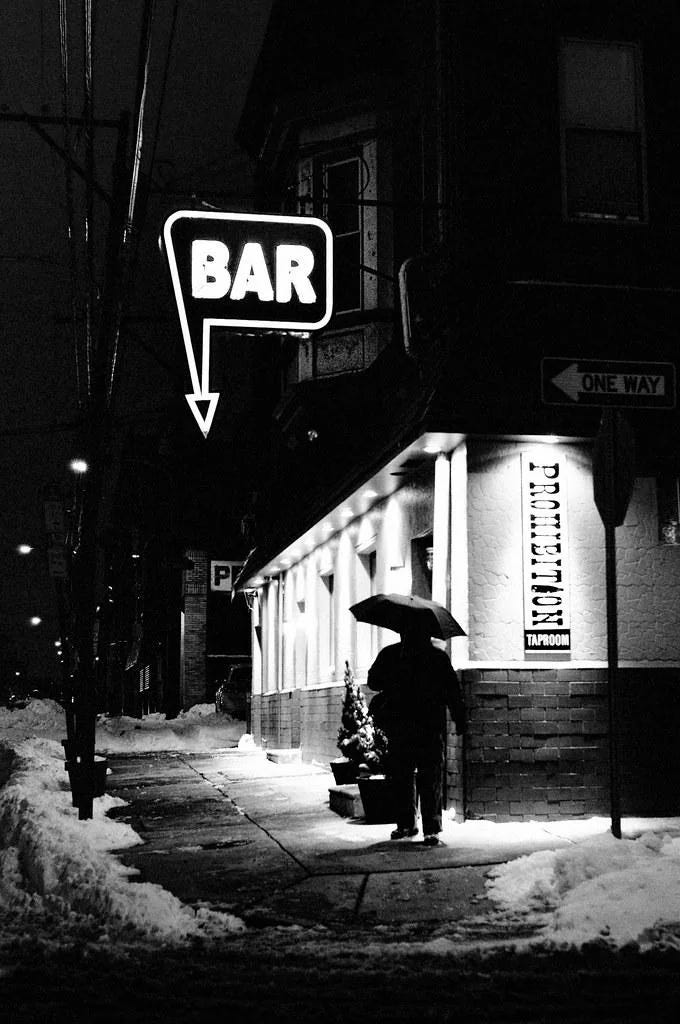

What is country music? To a young Willie Nelson, it’s whatever can earn you money to live. Broke, renting a cheap apartment on the edge of Houston, he spent the thirty mile work commute composing “Night Life.” Producer Pappy Daily didn’t think it was country and threatened to sue Willie for breach of contract if he released it. Pappy might’ve been right: it’s not country because Willie creates a new country on the song, a country born after midnight, where twang and jazz and blues all slink side by side, blurring racial and musical lines. Pedal steel player Herb Remington can hear it and see it too, a national anthem made from smoke curlicues and quiet defiance.

Willie Nelson - “Night Life” (1960)

The unnamed pedal steel player on Ferlin Husky’s “Living In A Trance” plays it painterly. These aren’t notes, these are colors: John Ford’s Monument Valley blooming onscreen in primal oranges and reds, the impossibly deep blue of endless skies, the parallel yellow lines of highway hypnosis. We aren’t zooming through the landscape anymore. We’re indisputably small here, spellbound.

Ferlin Husky - “Living In A Trance” (1961)

The Jamies’ “Evening Star”: another steel player (probably lap, not pedal), another mystery. A one-hit wonder of a vocal group bows out with an apocalyptic song. They follow the Santo & Jonny “Sleepwalkin’’ example, light and dreamy entertainment wrapped in reverb. But the steel player offers grieving, deathly wails instead of easy comfort, so soaked in echo it’s blinding. There were over a thousand atomic and nuclear detonations in the American West. There’s fallout clouding this song: “The evening star / is calling you.”

The Jamies - “Evening Star” (1959)

III. Ad Astra

100 million years ago, a meteorite smacked into land, creating a gentle bowl-shaped crater with a small mountain in the middle, a “rebound structure.” Centuries rise and fall, a road comes to connect Fort Stockton to Marathon, far west Texas in the heart of the Trans-Pecos. A small brown sign is raised on the side of U.S. Highway 385: ENTERING Sierra Madera Astrobleme. No further explanation.

In 1971, Gene Cernan and Jack Schmitt explore the region, taking geological samples and practicing for a very important mission. Barely a year later, they’re bouncing around the moon as part of Apollo 17, the last humans to do so. The West, the most moon-like landscape, full of astroblemes, astronauts, astrologists, and amateur astronomers. Where, on clear nights, the moon is so big and so close you could touch it.

In stadiums, in dorm rooms, in lonely cars tuned to the right station in 1973, you could touch the moon. Pink Floyd—pioneering “space rockers”—show millions The Dark Side Of The Moon. First seen by Apollo 8, Pink Floyd journeys further into the lunar night: it’s lunacy, it’s disillusionment, it’s the grand cosmic joke of mortality, it’s a triangular prism suspended in impossible blackness. Heartbeats. Clocks ticking, cash registers, voices, laughing, wailing—breathe. Dark Side starts here, trying to pour human frailty into song, something worth singing. David Gilmour ignites his Fender 1000 twin neck pedal steel, and suddenly we’re weightless. Country licks, stretched to infinity, by an Englishman no less. We’re far, far away from the ranch. We are trying to breathe in a vacuum.

Pink Floyd - “Speak To Me / Breathe” (1973)

On the far eastern edge of England, 1950s, a boy is growing up near a river in Woodbridge, picking up strange signals on his childhood radio. American Armed Forces, peppered across continental Europe, holding the East back from the West, bringing the American West with them and beaming it through their own radio station. Country music plays soft amid the static and distance. A young Brian Eno is transfixed.

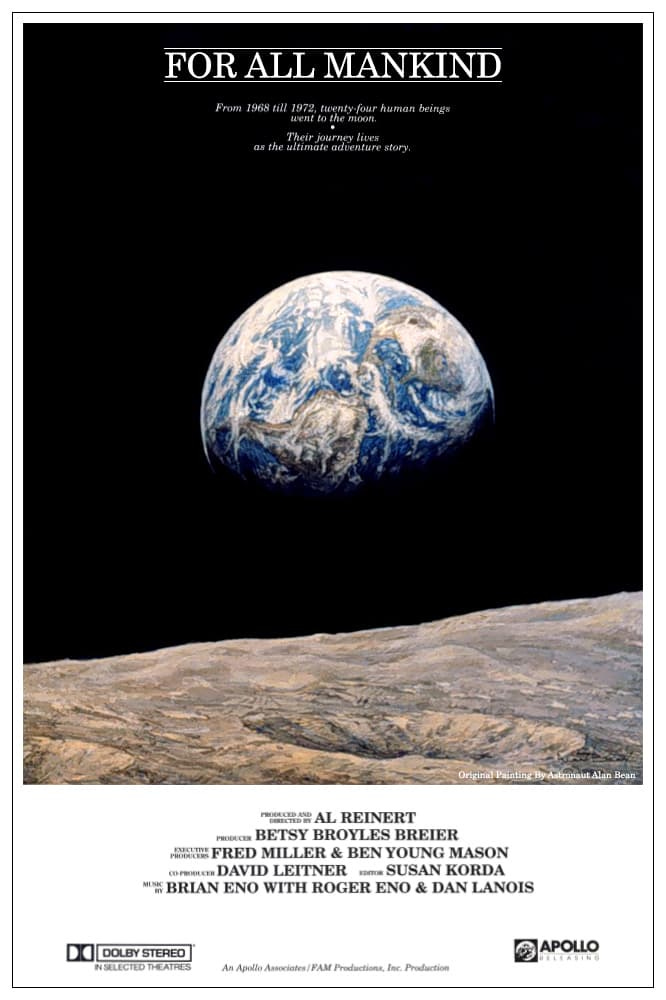

Eno grows up, goes to art school, grows his hair out, conjures his own strange signals from synthesizers, cuts his hair, teams up with a space oddity named David Bowie, keeps exploring, keeps moving. In 1983, he works with the Canadian producer Daniel Lanois, someone equally moved by country music and pushing the frontier further and further. They’re hired to compose the soundtrack to a wonderful, narrator-less film called For All Mankind. It documents the Apollo missions, 1968-1972, clip after clip of weightless awe. The Earth rising above the moon. The one small step, the one giant leap. Apollo 13’s brush with fate. The falling back to Earth. How do you soundtrack this? With desolate soundscapes, yes, tapping into the loneliness and the fear of that loneliness. But also, with that countrified, cosmic pedal steel.

Brian Eno, Daniel Lanois, & Roger Eno - “Weightless” (1983)

Eno: “what I find impressive about [country] music is that it’s very concerned with space in a funny way. Its sound is the sound of a mythical space, the mythical American frontier space that doesn’t really exist anymore…it’s very much like ‘space music’ — it has all the connotations of pioneering, of the American myth of the brave individual, and that myth has strong resonances throughout.”

Spectral synthesizers, the very definition of celestial, rise into view. A loping, subtle beat. A solitary pedal steel emerges over the grey ridge, crying, sliding, bathed in heaven’s thick reverb. It’s a “Deep Blue Day,” the blue of the “pale blue dot.”

Brian Eno, Daniel Lanois, & Roger Eno - “Deep Blue Day”

Carl Sagan: “From this distant vantage point, the Earth might not seem of any particular interest. But for us, it's different. Consider again that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every ‘superstar,’ every ‘supreme leader,’ every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.”

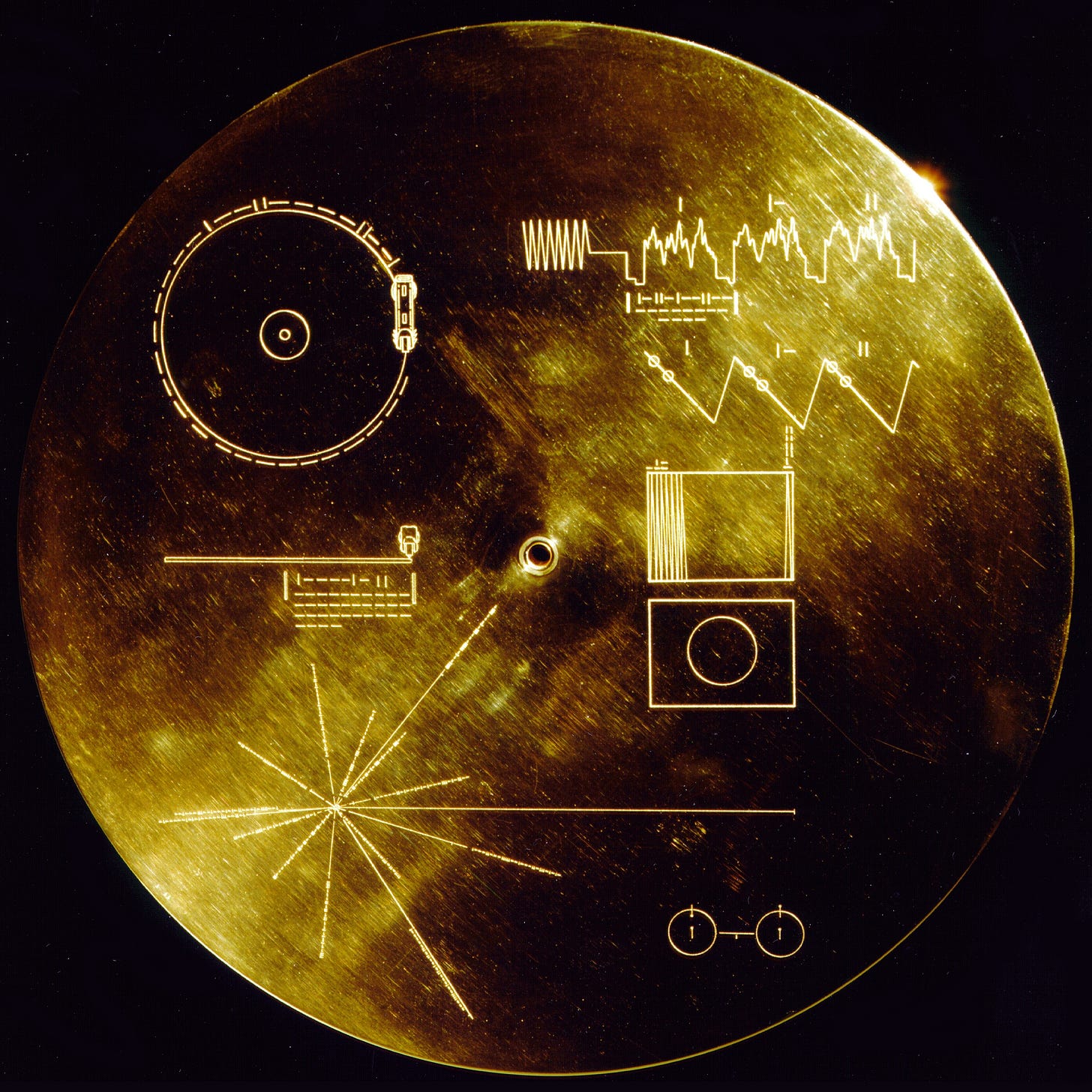

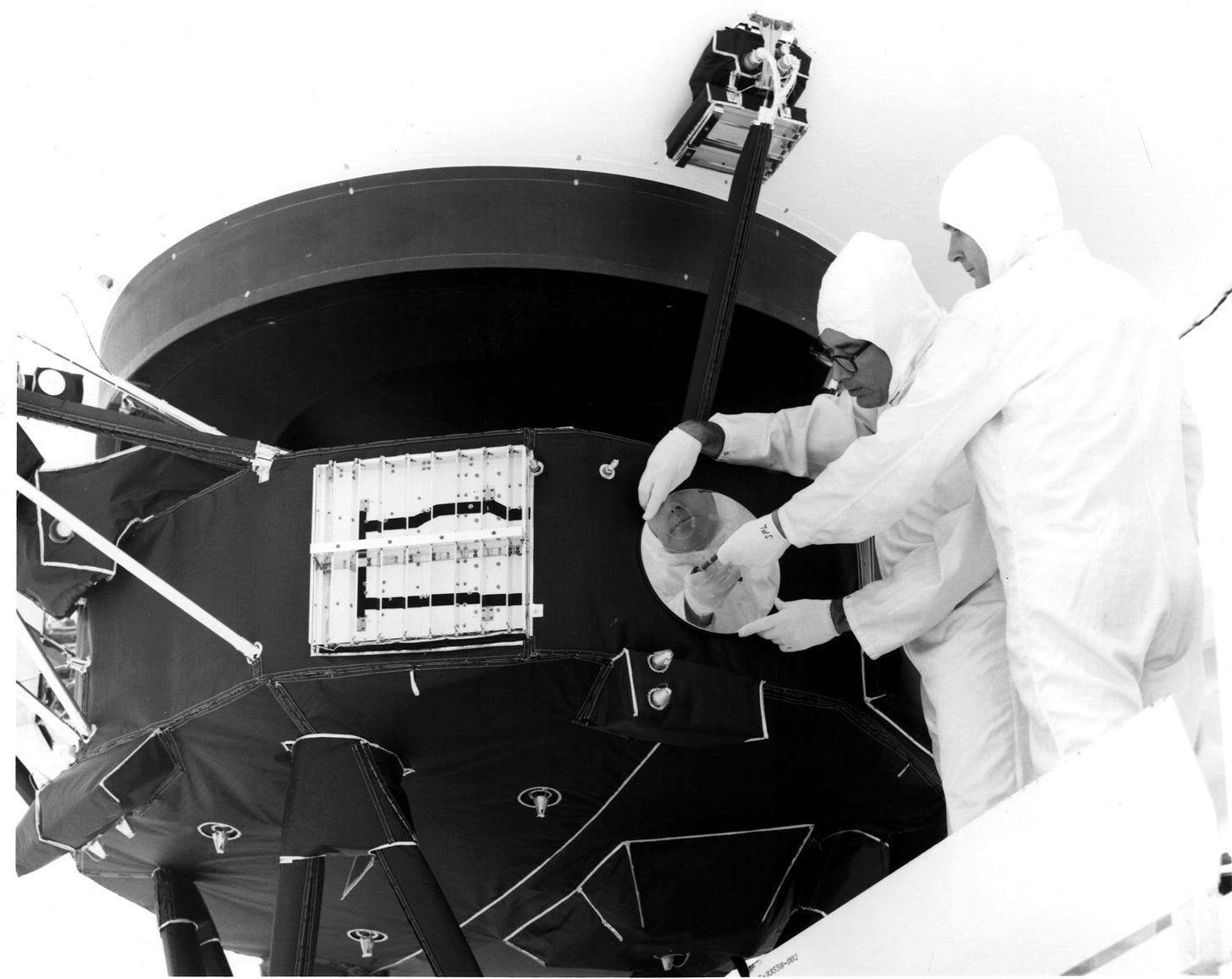

In 1977, Carl Sagan helped create the first interstellar mixtape. The Voyager Golden Records were two identical gold-plated records filled with sounds of Earth: “frogs, crickets, volcanoes, a human heartbeat, laughter, greetings in 55 languages, and 27 pieces of music.” The pair were launched on the Voyager 1 and 2 probes as time capsules and human greetings to our possible distant neighbors.

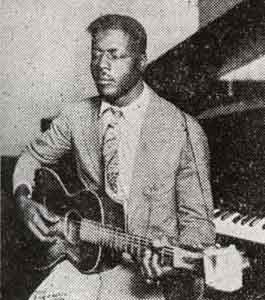

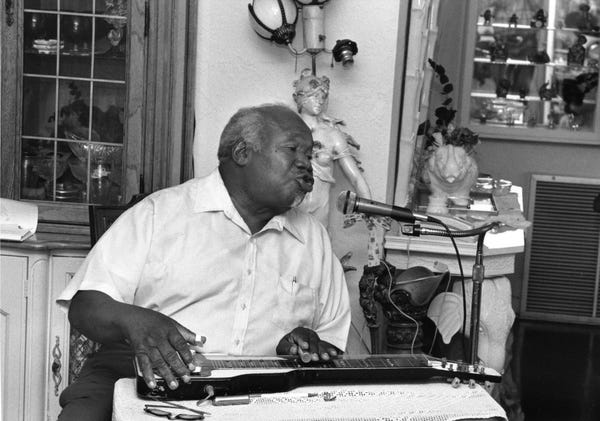

The usual Western musical suspects were included—Bach, Mozart, Beethoven—but NASA consultant Timothy Ferris suggested something more raw: Blind Willie Johnson’s “Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground.” Recorded in Dallas in 1927, the song highlights the Black, Christian, American experience that emerged from plantations, back porches, gospel revivals, and juke joints throughout the American South in the early 20th century.

It is a wordless take on an old hymn, but you get the meaning immediately, even without the song title. Johnson moans, groans, and cries through the song, every utterance shadowed and urged on by his slide guitar. True, it’s not a steel guitar, but Johnson uses a different kind of steel. Instead of a bottleneck slide, he uses a knife. He scrapes at the strings and carves the song out of the air. If Mozart aspires to the heavens, Blind Willie Johnson shows what life for a lot of humans is actualy like down in this cold dirt. And yet, like Mozart, he can transcend too.

Blind Willie Johnson - “Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground” (1927)

Blind Willie Johnson was born in the 19th century, the son of a sharecropper. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Blanchette Cemetery, in Beaumont, Texas. His music is currently aboard the farthest human-made object from Earth, traveling through interstellar space.

Are we alone? Early one Boxing Day, 1980, strange lights appear deep in Rendlesham Forest, a few miles east of Eno’s childhood village of Woodbridge. Lieutenant Colonel Charles Halt describes a glowing object, possibly metallic, moving—sliding?—horizontally. Nearby farm animals are in a frenzy. Astronomers attribute it to debris from a meteorite burning up in the atmosphere. Halt, in sworn testimony, still believes he saw it, that it’s been covered up by U.S. and U.K. authorities.

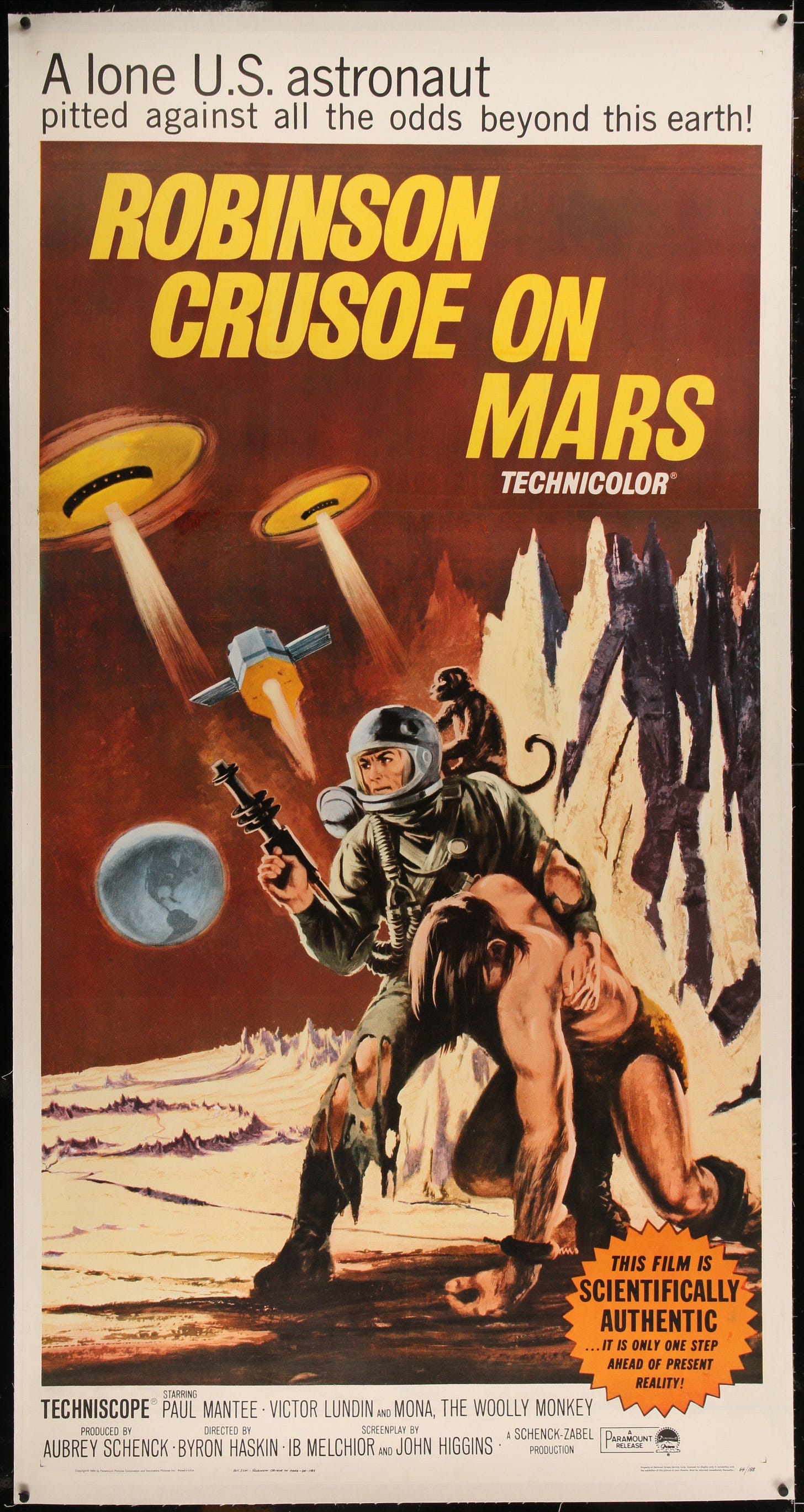

Sixteen years earlier, Robinson Crusoe On Mars is in theaters, a schlocky sci-fi movie filmed in the Martian-esque Death Valley. Its menacing flying saucers zoom in at the tail end of America’s first alien obsession phase, with UFO sightings all over the West and Hollywood-aided UFO fear all over movie screens.

This same year, Pete Drake’s “Forever” is burning up the charts. It’s released only a few years after a hit version by a cosmically-inclined vocal group: the Little Dippers. But Drake’s take flies past familiar. A country music session ace, Drake runs his pedal steel through a bizarre contraption called a talk box. There he is on TV, putting a plastic tube in his mouth and singing, breathing through the pedal steel. It’s downright alien. Man and machine are finally one.

“You don't actually say a word,” Drake explains. “The guitar is your vocal cords, and your mouth is the amplifier.” Postwar America is awash in conservatism, culturally, socially, and politically. But there’s this emergent force endlessly pushing towards a new world. The culture glides quickly, irresistibly. Even that keeper of tradition, country music, can’t drag its boot heels forever. The television cowboys and cowgirls cast nervous glances at this new alliance.

IV. The Wheel Turns

Everything breaks wide open. Hippies in the streets, assassinations on TV, death and dying in distant jungles. The old outpost of Hawaii is suddenly a staging area for the Vietnam War. California, the American West of dreams, convulses with drugged inspiration, with change. But even among the hippies, some traditions get smuggled in. In 1968, the Byrds do the unthinkable: ditch the acid in favor of the Grand Ole Opry. Sweetheart Of The Rodeo is a commercial flop for the once high-flying Byrds, somehow pissing off both hippies and the country establishment at the same time.

Gram Parsons and Chris Hillman leave the Byrds before the year’s up and form the Flying Burrito Brothers (there’s still some blotters tumbling in their pockets). They recruit a former stop motion animator—his fingerprints are all over Gumby and Davey And Goliath—named Pete Kleinow.

He’s “Sneaky Pete” in this new Brotherhood, armed with the eight-stringed Fender 400 pedal steel. Parsons and Hillman provide the close-knit harmonies, and Sneaky Pete baptizes the hippies in honky tonk. To keep the Southern California crowds on the Brothers’ side, he drags the steel through fuzzed-out distortion, echo, and tremolo.

The Flying Burrito Brothers - “Wheels” (1969)

There’s a tension at the heart of the Brothers. Here they are, dressed like cowboys, but their Nudie suits come embroidered with pot leaves and pills. They’re suspicious of the new world: “we’ve all got wheels to take ourselves away / we’ve got telephones to say what we can’t say.” But Sneaky Pete’s steel is forging that new world right under their boots. He’s dive bombing, he’s pioneering, he’s tripping. Parsons, the co-pilot, pulling Black and White music together under a new flag: this is Cosmic American Music.

“Now when I feel my time is almost up / And destiny is in my right hand

I’ll turn to him who made my faith so strong / Come on wheels, make this boy a man.”

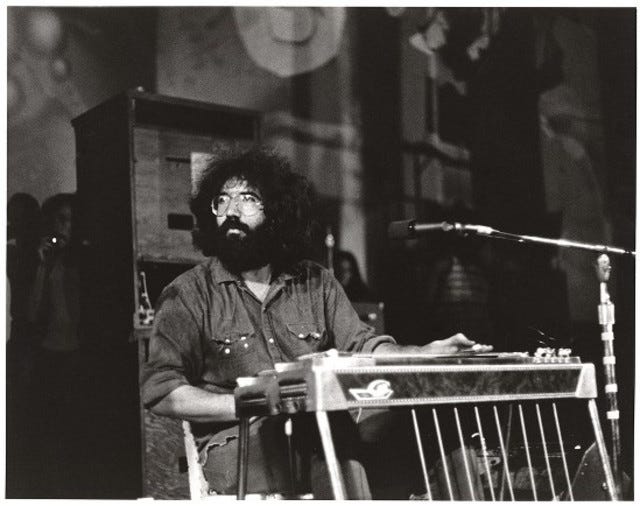

A few hundred miles north, a fellow charmer named Jerry Garcia is feeling the same faith. His music with the Grateful Dead is certainly cosmic and American, stretching out Motown classics and bubblegum Buddy Holly hits alike into strange shapes. He’s also interested in resurrecting country music from its cornpone masters in Nashville. So Garcia sits down and teaches himself how to play the pedal steel, using Sneaky Pete as his template. By the dawn of the new decade, the Dead have two hit albums featuring Garcia’s new skill. Gone are the acid-drenched electric jams. In their place, the Dead quietly venture into the psyche’s interior, the American West of the mind. Like his Brothers down south, Garcia is interested in wheels—but the spiritual kind, not automobiles. His steel guides the ear towards the heavens.

Jerry Garcia - “The Wheel” (1972)

The karmic wheel, the Hindu cosmology. The ever-present, the ceaseless turning and churning of the cosmos. The rise and the fall and the rise again. You can’t let go, you can’t hold on, you can’t slow down. “If the thunder don’t get you / then the lightning will.”

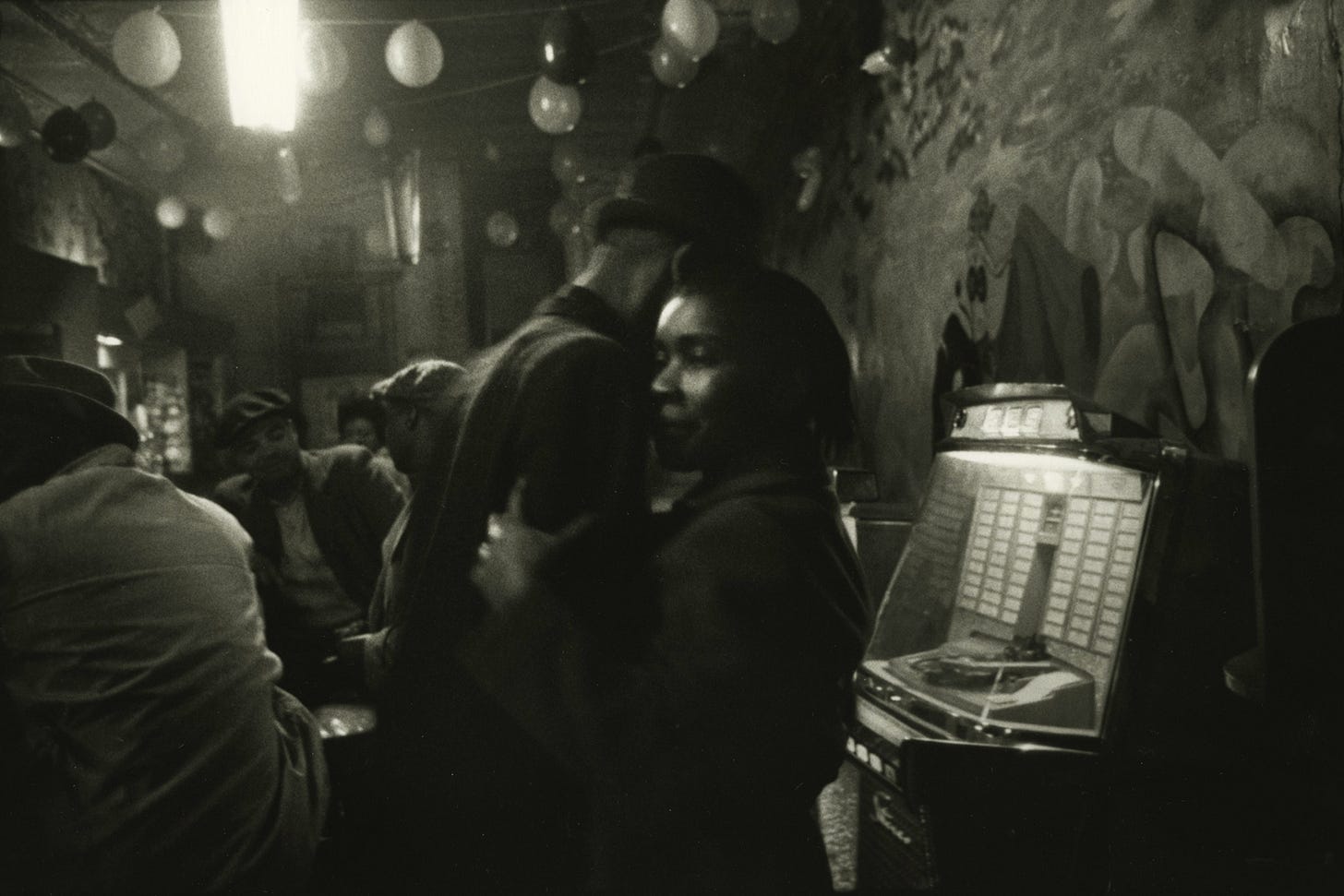

Lightning—or the spirit—struck in Philadelphia in the 1930s. The steel guitar turned sacred thanks to Willie Eason. “His brother, Troman, had a lap steel because of the Hawaiian-guitar craze,” says Chuck Campbell, a later-generation sacred steel player. “Behind his brother’s back, Willie would take it to the church and mimic the voices.”

It was the Church of the Living God, a breakaway Black Pentecostal church with affiliates all over the Eastern seaboard and South. Soon, the steel slid into the church bands in place of the organ and atomized into differing styles: a slower, boogie-woogie sound in the Jewell Dominion of the Church and the hard-driving style of the Church’s Keith Dominion. The important thing? Feeling the spirit. Rock and roll starts here, where Saturday night meets Sunday morning. The steel is the midwife, the living God.

Sonny Treadway - “This Is A Holy Church” (1997)

The human voice is mimicked by players like Aubrey Ghent and set loose on steel strings. Pete Drake told us: “The guitar is your vocal cords, and your mouth is the amplifier.” And in the church, there is a sacred audience listening in.

Aubrey Ghent - “Just A Closer Walk With Thee” (2010)

V. Terra Incognita

Thousands of miles away, the steel snuck into India. A Hawaiian named Tau Moe got there in the late 1920s and lived in Calcutta from 1941-1947. He performed and taught his Hawaiian style to curious neighbors while also building and selling steel guitars for musicians. And when the sliding style first appeared in Indian music, it seemed a divine match. In Indian music, sliding notes are common. The sitar, veena, violin, and shehnai all bend, exploring microtones and subtle emotional resonances in and around the notes. The steel was a natural dance partner and started appearing in Bollywood film soundtracks in the ‘40s. By the ‘60s, it was merging East and West with glee. Consider “Aao Twist Karen” from the 1965 film Bhoot Bungla, wherein steel player Kazi Aniruddha does a decent rock and roll imitation before creating his own subcontinental sock hop.

Kazi Aniruddha - “Aao Twist Karen” (1965)

With its Spanish feel and accordion, “Meri Bhigi Bhigisi” wouldn’t sound out of place in an Ennio Morricone spaghetti western. An absolute culture clash.

Kazi Aniruddha - “Meri Bhigi Bhigisi” (1971)

Then there’s Valentine “Van" Shipley. He was India’s first electric guitarist, playing and appearing in dozens of films beginning in the ‘40s. Dressed as a cowboy, his slide technique is brash, smuggling American country and blues licks inside popular film tunes.

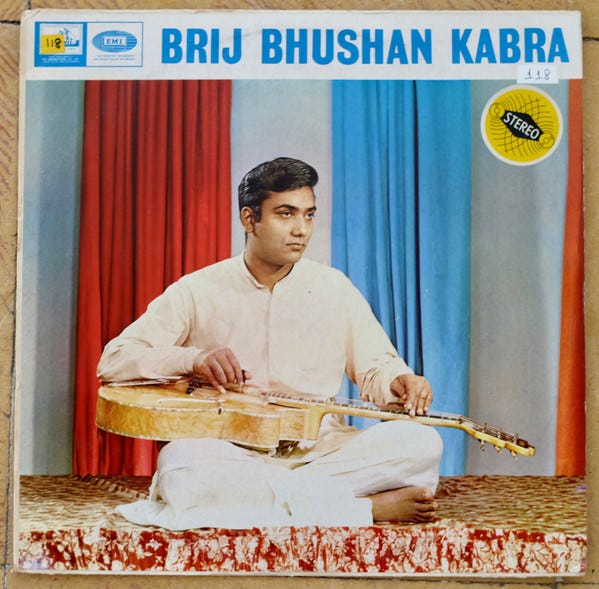

The slide changed shape when it hit Hindustani classical music. A young geologist named Brij Bhushan Kabra discovered the Hawaiian steel on a visit to Calcutta. After acquiring one, he promised his father that he’d only play classical music, and he kept his promise, to a degree. But curiosity also made him take a standard Gibson Super 400 guitar, raise the bridge, add drone strings, and play it like a lap steel.

It was an ingenious invention. Kabra could slide between East and West while keeping a steady undercurrent. In 1968, he debuted his Indian slide style on Call Of The Valley, one of the most popular Hindustani classical recordings of all time. The ragas are powerful and gorgeous, an interplay between Kabra’s slide, the flute-like bansuri, and the harmonic santoor, a type of hammered dulcimer. Kashmir, merging with Appalachia. It found a huge audience in the West, cited by Beatles, Byrds, and Dylan as inspiration. Like in churches and dancehalls and hippie get-togethers in America, the Hindustani slide became a spiritual tool. Greeting the divine in the valleys and peaks of the Western Himalayas.

Hariprasad Chaurasia, Brij Bhushan Kabra, and Shivkumar Sharma - “Ahir Bhairav/Nat Bhairav” (1968)

Brij Bhushan Kabra trained a student named Debashish Bhattacharya in the slide technique, and he’s taken the instrument even further. His chaturangui is a 22-string marvel, an archtop guitar with six melody strings, four drone strings, and twelve sympathetic strings struck with the forefinger.

Bhattacharya is adamant about sharing: “These are cross-cultural instruments for jazz and blues slide guitarists, as well as those playing ragas—which we believe is not ethnic music for one part of the world, but rather global music for everyone to share.” Here he is at NPR with his daughter and brother, lightning fast on the chaturangui and beaming with joy.

“Onstage, when I get deep into the raga, I forget everything. First, I forget where I’m sitting. Then I forget what I’m doing. And, finally, I forget my name and who I am.”

In the 1960s, another curious collision happened. Jim Reeves, a former minor league pitcher-turned slick Nashville crooner, became famous in Nigeria. The West African nation took to “sentimental music”—any Western music not made for dancing. But country music, with its Christian morality and that odd, spiritually-minded steel guitar, hit hardest.

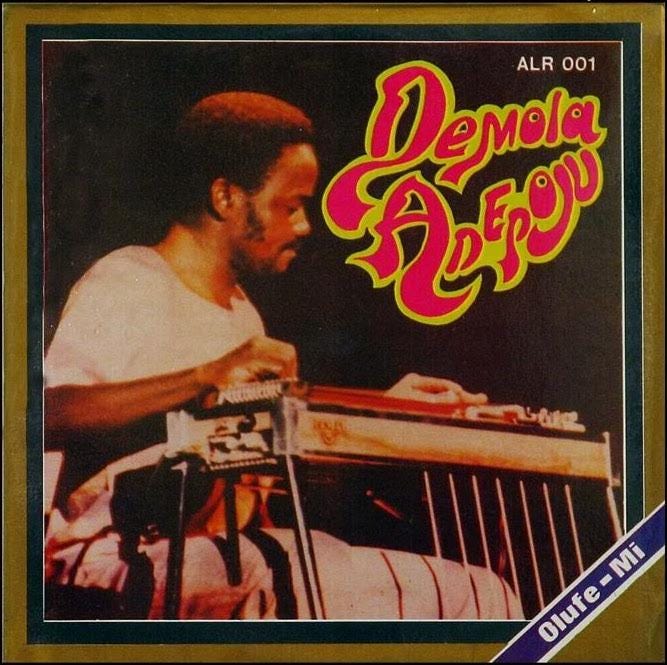

It was in this cultural delta that Demola Adepoju first fell in love with the instrument. Yet in his hands, it’s not a culture clash; it’s an ascension. Adepoju joined Nigeria’s king of juju music, King Sunny Adé, in the early ‘70s with a simple lap steel before buying a few Emmons and Sho-Bud pedal steels in England. With no example except his ears, he taught himself how to play one of the most difficult instruments ever, devising his own tuning system to fit juju’s elliptical style. He played barefoot. And in 1982, he took flight on Juju Music, King Sunny Adé’s introduction to the West. There’s Adepoju soaring over, under, between the polyrhythmic beats of “Ja Funmi.”

King Sunny Adé - “Ja Funmi” (1982)

Adepoju’s ’85 solo album continues this spectral blend, turning the pedal steel itself into a “rural synthesizer.”

Demola Adepoju - “Olufe-Mi” (1985)

Most summers when I was a kid, we used to drive from Dallas five hours southeast to Galveston Island for vacations. Crossing over the Causeway, when the palm trees first rose into view on the far side, the brown pelicans cruising parallel to the car, we listened to a specific soundtrack: a cassette tape of Paul Simon’s Graceland. I’m not sure why my parents chose this in particular, but it happened enough times for me to permanently see Galveston’s faded glory in my mind anytime I hear the album’s blend of South African and American styles. It fits, somehow. Out my window, an island that has seen better days; in my ears, stories of divorced pilgrims and Memphis pilgrimages, poor boys and zydeco dances, lasers in the jungle somewhere, angels in the architecture.

We’ve clacked over the last Causeway bumps, coasting down Broadway, and “Graceland” bubbles up with its rubbery bass and 2/4 rhythm. It’s a song I connected to country music even as a kid, despite the song’s African feel and players. And there, hovering somewhere over the song: it’s Demola Adepoju and his pedal steel, worked by bare feet. The melody he plays is so delicate. He’s not glorifying and transgressing like in King Sunny Adé’s band. He’s connecting country music to blues, the American South to West Africa, the suffering of the Middle Passage to the sorrowful bent and slid notes of the ancestors. He’s taking the sound back home.

Paul Simon - “Graceland” (1986)

VI. Eternalism

In late ‘80s UK, home was a rave in a warehouse or empty field. All-night dance parties—fueled by acid house and its namesake drug, along with MDMA—unleashed a torrent of joy, optimism, and creative potential for a new generation. Electronic music was the driver and innovator of culture, with new mutations spawning every few months: hardcore, jungle, drum and bass, each pushing tempos and experiences to more intense places. But even the electronic innovators sensed balance was needed. Enter: the chill-out room. These were spaces removed from the dance floor that offered couches, bean bag chairs, and a calm environment. Or as raves seeped into the English countryside, chilling out meant stretching out in a grassy expanse, watching the sun rise.

Chill-out music came first, though. Alex Paterson (of the influential UK group the Orb) first experimented with running old synthesizer and prog rock records through dubbed-out effects in a VIP bar run by Paul Oakenfold. What was meant to be mere background music turned into the main event, due to its spontaneity and irreverence. “Ambient house,” as the style came to be called, could transport you far, far away. “This was music not for coming up, or even the thrilling rush associated with Ecstasy, but for the inevitable comedown,” writes Matt Anniss.

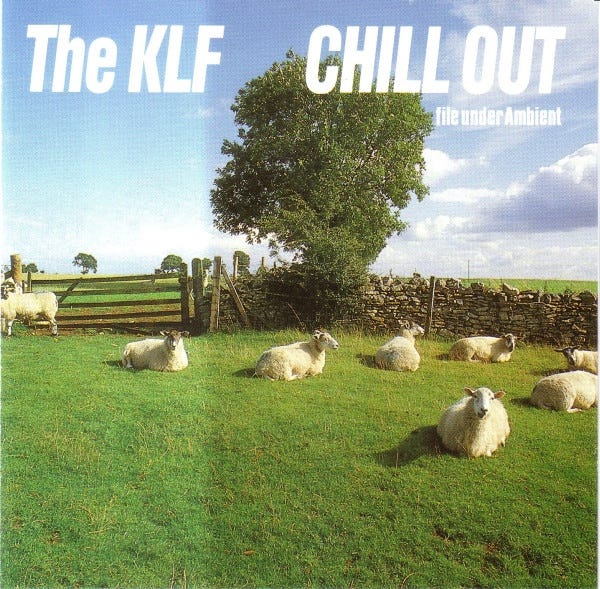

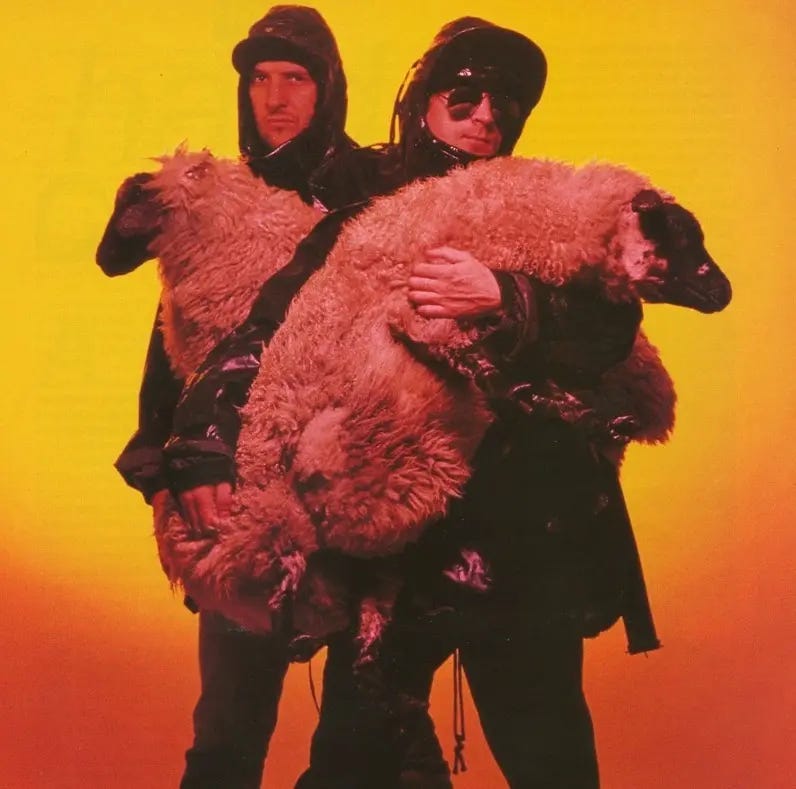

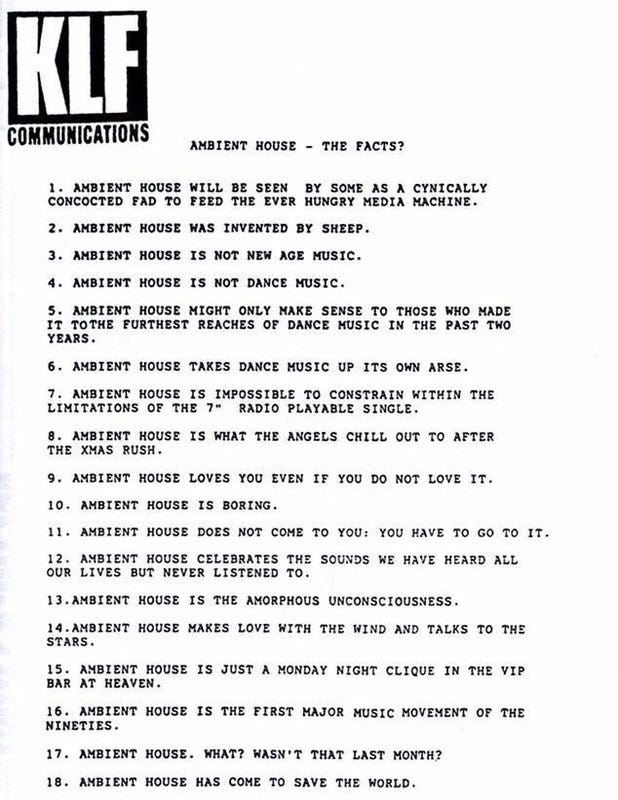

The KLF christened the style with the totemic Chill Out in 1990. The duo of Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty were the court jesters of the British rave scene, notorious for setting a million pounds of record company money on fire (literally). Chill Out came from this cheeky contrarianism and Drummond and Cauty's collaborations with Paterson. It’s a true sonic experience, a forty-five minute journey that unfolds in your imagination. Drummond and Cauty stitched the whole thing from samples, pilfering from anywhere and everywhere to create their own sort of nowhere. Sound effects records, Pink Floyd soundscapes, radio broadcasts, and Van Halen guitar solos are all treated equally. Juxtaposition is the architecture here: train sounds and sheep bleats; raving preachers and Tuvan throat singing; serene drones and pounding synth arpeggios. It’s too interesting to be purely ambient, and too rhythmless to work on the dance floor. But in a space dedicated to coming down, to resetting, it could be transcendent. There is a Cageian idea at work: the pleasure of just listening to sound. Sound becomes its own music. “Ambient house celebrates the sounds we have heard all our lives but never listened to,” the KLF wrote in their original press release for Chill Out.

There’s a loose road trip theme to Chill Out. The train and car sounds carry you from sample to sample like telephone poles passing out your window. The titles for each section are incredibly evocative: "Brownsville Turnaround on the Tex-Mex Border,” "Pulling out of Ricardo and the Dusk Is Falling Fast,” "3 A.M. Somewhere out of Beaumont,” "The Lights of Baton Rouge Pass By.” “I love maps and atlases and I love place names, and I just sat down with the atlas and picked, you know, and saw the journey that it was and it all seemed to fit,” Drummond told X Magazine in 1991. "I've always loved those [song] titles like 'The Lights Of Cincinnati' and, you know, ‘Galveston’…American cities and towns and places, to us over here, have a real romantic feel to them.”

Chill Out is partially a trip up the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana, played for ravers half a world away trying to detox in some muddy field in the English countryside. Dislocating, but oddly moving. More so with the appearance of our old friend, the pedal steel guitar. An Australian player named Evil Graham Lee hovers in the background before breaking like the dawn on “Madrugada Eterna.”

The KLF - “Madrugada Eterna” (1990)

“Madrugada Eterna,” Spanish for “Eternal Dawn.” And there’s something eternal about his playing, fed through effects and weaving in and out of synth chords and Pink Floyd quotations. The entire album is horizontal, like the pedal steel, and is meant to be heard while horizontal. It places discrete contexts side-by-side and says, “these are all of equal value.” It’s an alien sound and idea, something almost angelic: we are all one. “The KLF’s idea of chilling out isn’t a passive stupor—it’s a kind of heightened awareness,” writes Philip Sherburne. In that awareness, Lee’s pedal steel liquifies time and space. The beauty it brings is painful, like the sun breaking over the morning, like awareness dawning.

The pedal steel submerges, resurfaces a few minutes later as the Greek chorus for none other than Elvis, that Memphis pilgrim. A sample of “In The Ghetto” makes an oddly moving appearance, the American icon repeatedly intoning “as the snow flies” before being swallowed up by birdsong and waves.

The KLF - “Elvis On The Radio, Steel Guitar In My Heart” (1990)

Like the pedal steel, the album was cumbersome to play. Drummond and Cauty sampled and mixed everything in real time, meaning that they had to start all over again—as they did several times—if any mistakes were made. And like the pedal steel, Chill Out is awe-inspiring in this aliveness.

When picking the cover, Drummond and Cauty wanted something rural, something distinctly English to capture rave’s own odd juxtapositions. It’s a handful of sheep, serenely gazing out as the world speeds by. Zen-like, or poking fun at rigid followers of fashion?

"When somebody takes the stage [at a pedal steel convention] and plays something other than country, people get up and walk out,” Tom Bradshaw, onetime publisher of Steel Guitar magazine and instrument player/repairman lamented to Jesse Jarnow. There’s an uneasy power lingering in all those levers and strings. This instrument is a great connector of styles, of peoples, of cultures, even with the reactionaries tugging at its pedals. The pedal steel is a threat, hard to play and easy to misunderstand its destiny. Its look still has that mid-20th century futurism to it, but the pedal steel might be the perfect vehicle for the 21st.

Susan Alcorn was driving her car down the numbing freeways of Houston on the way to a country gig, pedal steel in the back, when she heard the French composer Olivier Messiaen’s “Et Exspecto Ressurectionem Mortuoram” on the radio. She was so moved, she had to pull over. In 2006, Alcorn—who had been slowly sneaking in John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler into her playing since the ‘80s—composed “And I Await The Resurrection Of The Pedal Steel Guitar” as an ode to this experience. This ain’t no honky-tonk. This is hardcore art music, dissonant chords slithering around one another, a gathering cloud of sound releasing the full potential of the pedal steel. “In this piece I wanted the whole body of the instrument – the legs, the pedals, the wood, the strings, tuning keys, bridge and nut, and pickup – to tell its story,” she writes. “I know the time will someday come when the steel guitar will again sing its own song – a song with a sense of majesty, ecstasy, and beauty approaching that of Messiaen.”

Susan Alcorn - “And I Await The Resurrection Of The Pedal Steel Guitar” (2007)

Glasgow’s Heather Leigh takes up Alcorn’s call, and to a certain extent, Pete Drake’s. She doesn’t need a talk box; instead, her pedal steel shadows her vulnerable voice from the highest highs to the deepest depths. It sounds like she’s singing with two voices. “Fairfield Fantasy” moves warily on a landscape of microtones, shifting like pack ice.

Heather Leigh - “Fairfield Fantasy” (2015)

"I don't think you can overstate the importance of the fact that, when you ask who's pushing the instrument forward, the answer is there are these two women — Susan Alcorn and Heather Leigh,” Chuck Johnson told Jarnow. “More than any other instrument I know, the culture around [pedal steel] is so male dominated.” But in this new century, you don’t hear as much macho, whiz-bang pyrotechnics on its frets. The pedal steel can be used softly, subtly. Johnson himself opts for a painterly approach. On 2017’s Balsams, he pulls Rothkos from layered, looped, and effected pedal steel passages.

Chuck Johnson - “Calamus” (2017)

Beauty is the fountainhead of life, Elaine Scarry writes in On Beauty. “It makes us draw it, take photographs of it, or describe it to other people.” Or play it. In this smeared twang, Johnson connects the oranges of Monument Valley to the color field painters to the rocket glares of the Apollo missions. Country—the land, the sound—as ambience. Another ascension.

Chuck Johnson - “Riga Black” (2017)

There are others mapping these new constellations. SUSS makes its own form of ambient country with soundtracks to imaginary, cosmic spaghetti westerns. When he isn’t playing with Margo Price, Luke Schneider moonlights as a high priest of psychedelic pedal steel. Will Van Horn has transcribed Aphex Twin’s tricky, glitchy electronica for the instrument. Daniel Lanois—onetime pedal steel lunar traveler—goes the other way and transforms the steel itself into glitchy electronica.

VII. Afar

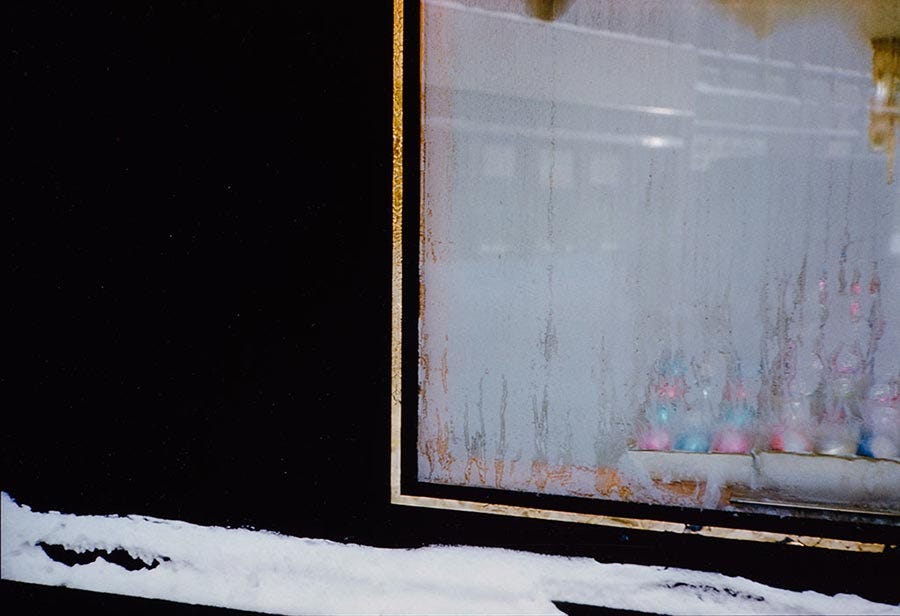

A railroad spike picked up by a Hawaiian kid eventually took us to outer space. Now we return to Earth, specifically the Trans-Pecos, a stretch of Texas highway 90, somewhere between Van Horn and Valentine. It is June 2022. I’m driving with my wife and dog, swooping down via Colorado and New Mexico.

A thunderstorm the color of every fear is rolling forward, unstoppable. Only way out is through. It is truly apocalyptic-looking, inching across the desert scrub from the northeast. There are no buildings to block our view. We feel too small. When it hits, it hits violently, dropping our speed down to a crawl because we can’t see the highway three feet in front of us. It’s terrifying. But a Texas thunderstorm tends to stay true to its restless character. After twenty minutes or so, it slithers away, and we can see the sun setting. We laugh nervously.

On the east side of Marfa, a few miles from Marathon, I spot snow on the highway shoulder. I’m awestruck—snow! In June?! It’s all over the road, quickly melting, and the arroyos are flooded, and this desert valley is suddenly a dangerous water chute. We inch our way around flooded embankments and icy patches. When we check into the hotel in Marathon, a little rattled, I ask about the snow, and the clerk laughs. “It’s hail.” So fierce it splattered into wintry piles. She says the Department of Transportation was called out to help some stranded motorists, stuck in water and battered by hail. I quietly thank the storm for slowing us down an hour previously.

In our room, we eat a hurried dinner before the kitchen closes—it’s the only restaurant in town. My wife and the dog start going to bed, but I feel this need to stay up. We’re staying at an old motor court. I sit out on our porch, which is part of a shared arcade looking into the courtyard. Swallows are furiously busying themselves before nightfall, zooming between their nests under the awning and the giant weeping willow in the courtyard’s center. From my seat, I can just make out the southern horizon. It’s flashing angrily with lightning, and I can feel the cool air whipping around the space as another storm begins its descent.

Harold Budd - “Afar” (1981)

My soundtrack to all this is “Afar” by Harold Budd on my headphones. Budd, in his deeply felt way, spilling out notes on his piano, as Chas Smith colors things in purples and deep blues with his pedal steel. Sometimes, the piece threatens to resolve into a slow-motion country ballad, but the chords wander away. I always loved the title to the album it’s from: The Serpent (In Quicksilver). This quicksilver music, this serpent following its own intuition.

My wife is pregnant. I’m deeply afraid, but I’m finding it hard to square up to that fact. So I’m watching this storm from afar, not wanting to get wet, letting this music ooze and pool around my insides. It’s dripping into those unnamed spaces that only music can get to. There are times in the previous years where I’ll put on a record and just cry for no reason. I can’t say it. I have to hear it and feel it.

Though I don’t know this yet, sitting on this West Texas bench, the pandemic era began the annihilation of my former self. I feel twitchy, angry, and deeply, vaguely afraid from the moment I wake. I move in a fog. I am mean to myself and those I love. When my daughter is born in August 2022, the annihilation continues. It is so, so hard being a parent, especially in those early days. Somewhere in the fall, my former self finally lets go with a series of panic attacks. Slowly but surely, I begin to feel better, newer, sturdier. It feels like a miracle. I grieve my old self, the pandemic years, the forgotten dreams and lived nightmares.

That West Texas storm, that steel guiding “Afar” as I sat in Marathon, planted something. It connected all these sounds and sights, eras and cultures like a tree, like a scar of lightning slashing across the sky. I’ve worn many boots in my life—son, brother, husband, student, clean cut office worker, punk rocker, radio DJ, father—and the steel has shadowed me. It’s the first sound I remember: Hank Williams’ “Jambalaya” on cassette in the back of our Isuzu Trooper, aged 4 or so. It’s a sound I can’t forget. My body aches for it when I haven’t heard it in awhile.

“The weep of a pedal steel guitar is the sound of heartstrings being torn,” says the KLF’s Bill Drummond. Why do we subject ourselves to something so emotionally masochistic? To feel life, sliding through our veins, a river returning to the sea.

A neighbor friend’s aunt and uncle converted their garage into a sort of honky tonk, complete with bar and stage and wooden cafe tables and worn carpets with peanut shells ground into them. The uncle played pedal steel and one sat on the stage and sorta taunted/frightened me. I was scolded never to touch it, and I didn’t, much… In all the time I lived nextdoor to them, they only had one party in that fantastic converted garage; uncle Frank only plugged in and played his pedal steel one time. I still feel saddened by that here 35 or 40 years later.

Though I am an admitted failed pedal steel player, I still love the instrument and this paean to the steel is the best thing I've read (on any topic) in awhile. This deep dive into the instrument's history and its impact on modern music is beautifully written with a perfect mix of audio and images from some of my favorite musicians and photographers.